|

|

|

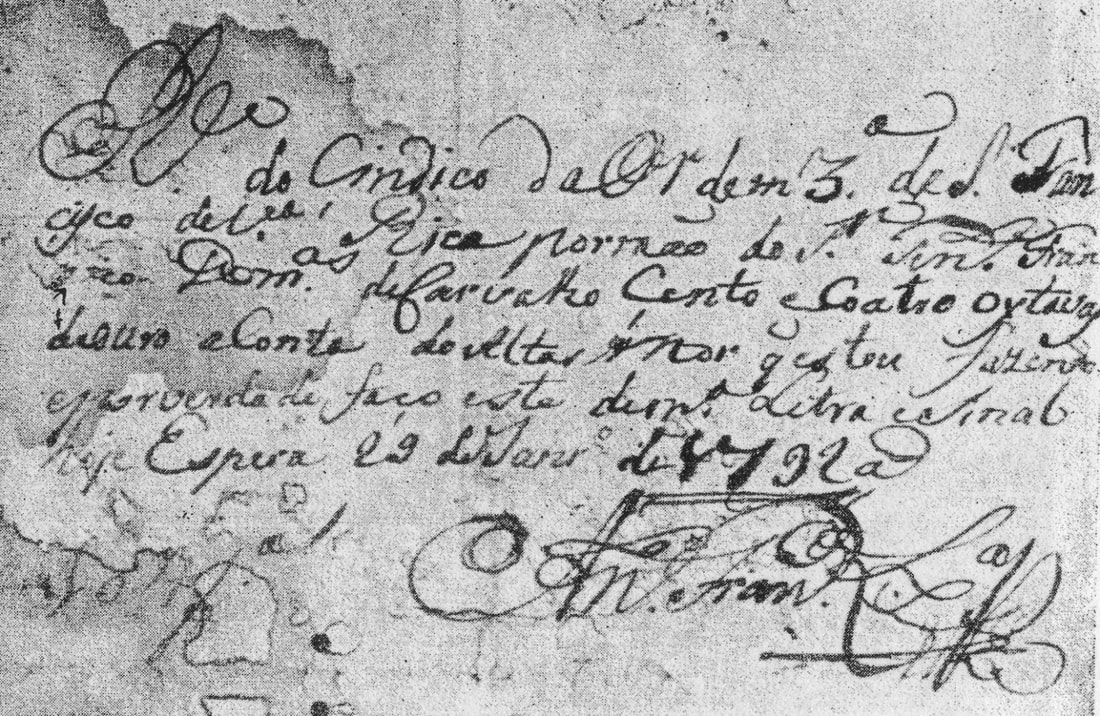

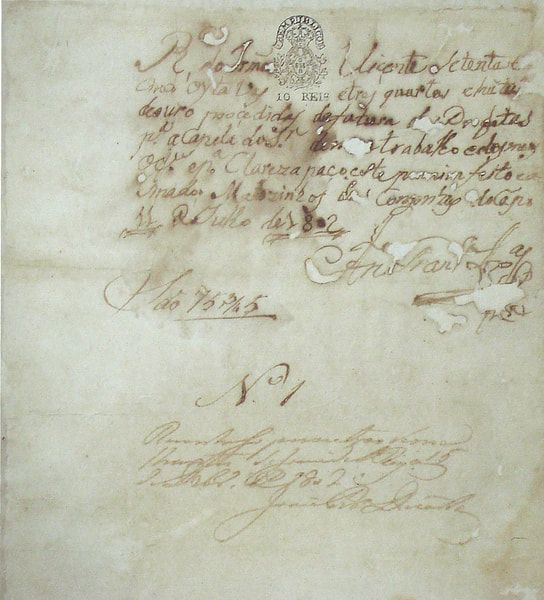

Was he disabled?While some scholars have claimed to have discovered documents that refer to Antonio Francisco Lisboa by the name "Aleijadinho," those sources have mysteriously vanished. One source from Lisboa's lifetime does, however, suggest that the artist might have suffered from physical ailments of some kind. In 1811 Wilhelm Ludwig von Eschwege, a German mineralogist, visited the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus de Matosinhos in Congonhas do Campo. Antonio Francisco Lisboa's role in sculpting the wooden figures in the Stations of the Cross chapels and the stone sculptures along the steps of the church is well documented.

Although he did not name the artist, Eschwege wrote of his visit: “The preeminent sculptor, who distinguished himself here, is a crippled man with lame hands, he has the chisel strapped on to himself and therewith carries out the most artistic works, but sometimes his drapery and figures are tasteless and disproportionate; otherwise, the beautiful facilities of the man, who was completely self-taught and never saw anything, are not to be mistaken.”

Bretas described the disease as beginning in 1777:

“Antonio Francisco lost all of the toes on his feet, which resulted in the inability to walk unless on his knees: the fingers of his hands atrophied and curved, and also ended up falling off, leaving him only the thumbs and index fingers, and even so almost without movement.” Neither Eschwege nor Bretas ever met the artist and Antonio Francisco Lisboa's continuing ability to sculpt, draw, and write suggests that his disfiguration was exaggerated. |

|

|

Resources |

Further ReadingTim Benton, and Nicola Durbridge, “’O Aleijadinho’: Sculptor and Architect,” in Catherine King, ed., Views of Difference: Different Views of Art (New Haven: 1999), pp. 146-177.

Amy Buono, “Antônio Francisco Lisboa [O Aleijandinho],” in Colin Palmer, ed., Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History: The Black Experience in the Americas, 2nd edition (Detroit: Macmillan Reference, 2005), 1293-1295. John Maddox, “The Aleijadinho at Home and Abroad: “Discovering” Race and Nation in Brazil,” The New Centennial Review 12, no. 2 (2012), 183-216. Tania Tribe, "The Mulatto as Artist and Image in Colonial Brazil," Oxford Art Journal 19, no. 1 (1996), 67-79. Rachel Zimmerman, "Church of São Francisco de Assis, Ouro Preto, Brazil," in Smarthistory, April 5, 2018, accessed April 18, 2018, https://smarthistory.org/sao-francisco-ouro-preto/. |

|

Cite this page as: Rachel A. Zimmerman, "Antonio Francisco Lisboa: Aleijadinho," in Minas Gerais Setecentista, April 18, 2018, accessed [date], http://www.razimmerman.com/antonio-francisco-lisboa-aleijadinho.html

|

Copyright 2018 Rachel A. Zimmerman