The Orman Collection

James B. Orman, governor of Colorado from 1901 to 1903, his wife Nellie and their son Frederick traveled throughout the United States collecting Native American objects and artworks along the way. Except for the work of Arley Woodty and Severino Martinez who are local contemporary artists, all of the objects on display stem from the Orman family’s collection.

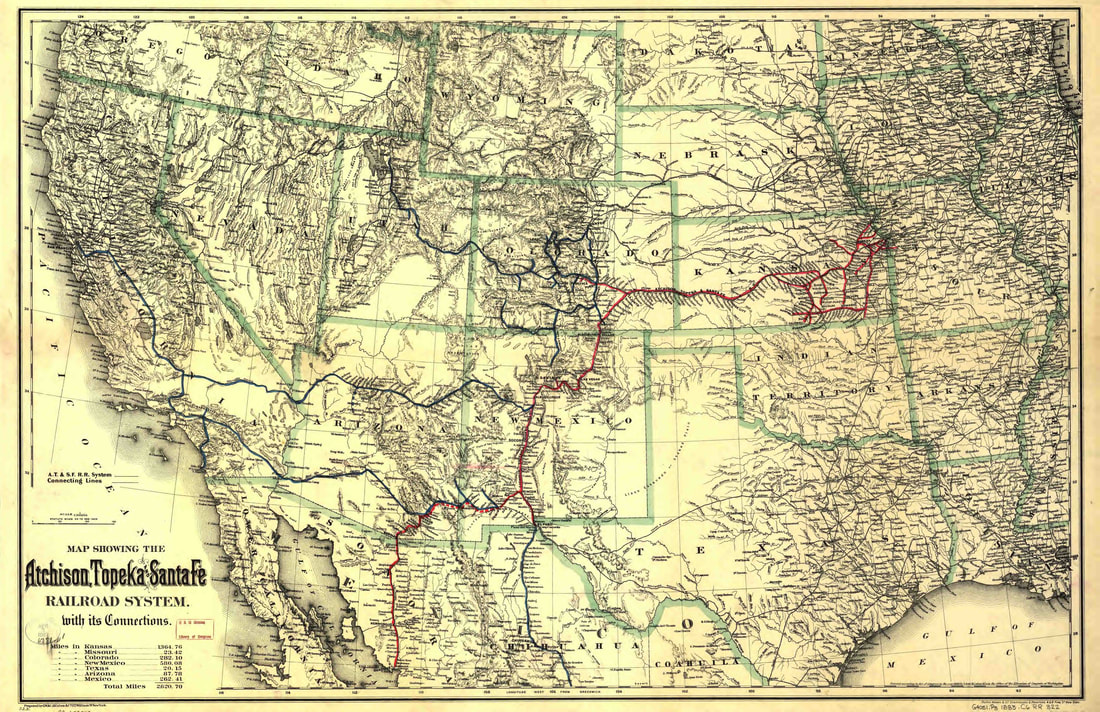

Railroads are central to this collection’s history. By the time that James Orman moved to Pueblo in 1874, the town was a major railroad hub. Orman was involved in the construction of many of the railroad lines that connected Pueblo to other parts of the country, including the Santa Fe line. The Santa Fe line ran through New Mexico, Arizona, and California, connecting indigenous artists throughout the Southwest with art collectors and tourists, the Ormans among them. Indigenous artists took advantage of this opportunity to expand art production and to financially support their communities. Artists adapted to the tastes of tourists, often melding tradition with innovation. Some invented new techniques, developed methods to work with new materials, and experimented with new visual effects and imagery. Often, artists used artworks found archaeologically as inspiration, reviving techniques and designs that their ancestors valued long ago. |

Copyright 2020 Rachel A. Zimmerman